Charlie Rees

saxophonist | composer/arranger | journalist

Charlie’s broad range of skills have seen him build an impressive resume in his young career so far. He has performed with internationally renowned artists like Richie Beirach, Alex Sipiagin, the Sirius String Quartet, and has worked with the London Jazz Orchestra as an arranger and player numerous times. Heavily influenced by the music of John Coltrane and the post-Coltrane generation of saxophonists, he splits his time between the UK-scene and Germany, where he plays periodically in a trio with German-based musicians Regina Litvinova (keyboards) and Tobias Frohnhöfer (drums).

He is also respected across the world for his work in jazz journalism. In his capacity as the Assistant Editor of UKJazz News (formerly LondonJazz News), a position he has held since 2022, he has contributed countless articles to the UKJN archive. Some of his journalistic highlights include interviews with Christian McBride, Curtis Stigers and Bob Mintzer, as well as an acclaimed five-part series on the life of saxophonist Steve Grossman.

Read Charlie's series on Steve Grossman

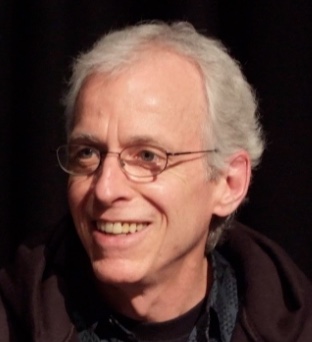

"Charlie’s series of written pieces on the music and the life of Steve Grossman are not just superbly researched, they also show a maturity, sensitivity and fine judgment when dealing with the saxophonist's complex personality."

Sebastian Scotney

Founder & Editor of London Jazz News

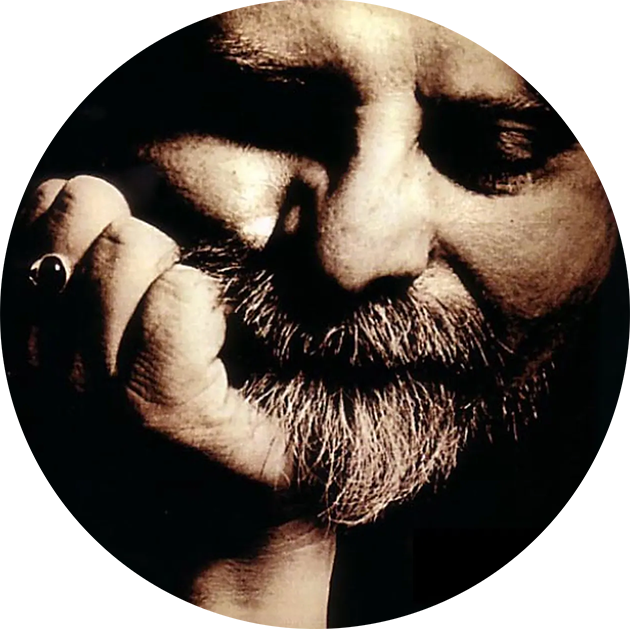

Among the post-Coltrane generation of saxophonists, Steve Grossman is regarded by many as having had the greatest raw talent. He set the saxophone world on fire when he burst onto the scene with Miles Davis in the late 60s, at only 18 years of age, then built on his reputation with the Elvin Jones Quartet in the early 70s. By the time his debut recording, Some Shapes to Come, released in 1973, his future looked bright as an emerging tenor heavyweight. But this was ultimately not to be, as he developed a pernicious drug habit that severely hampered his artistic development. He released a handful of quality recordings over the ensuing years and played on many great sessions as a sideman, but the output was inconsistent at best.

Though he lived to be 69, passing away in 2020, it is not hard to see how Steve Grossman has become an obscure name to younger generations, overshadowed by similarly talented and far more driven contemporaries like Michael Brecker and Dave Liebman. Most jazz historians pay little attention to his place as an innovator on the instrument (though Mark Stryker’s obituary is highly recommended), a reality for which he largely has himself to blame. Discussing Steve Grossman is a five-part interview series that aims to correct those aforementioned oversights and help to rebuild the tarnished legacy of his life and music.

Discussing Steve Grossman (1): Interview with Richie Beirach

“I remember him at jam sessions all over Manhattan, especially in Lieb’s loft on 19th Street. We played a lot of stuff together: A lot of free music, a lot of improvised music, some tunes. He had an amazing sound on tenor. He was ahead of everyone, I must say. It was him, Michael Brecker, Lieb, Bob Mintzer, Bob Berg… those were the guys, and he was the best one. I mean, best is a horrible word, but he was the most advanced and the most… he just had that sound! It was Sonny and Trane. Grossman was just ahead of us all. He was getting his own sound, his own way of playing.”

Read the Full ArticleDiscussing Steve Grossman (2): Interview with Dave Liebman

“At first, there was a little bit of a rivalry between us. And me being older, I thought it was my responsibility to cool it out. So we had a meeting at his parents’ house in Long Island. ‘We’ll be stronger together than separate’ and ‘you’ll be Trane and I’ll be Pharoah [Sanders]’, that was kind of our relationship. I played a little looser, he played all the vocabulary and everything.”

Read the Full ArticleDiscussing Steve Grossman (3): Interview with Gene Perla

"He’s the greatest sax player after John Coltrane. You know, I have a recording of Elvin saying that. Everybody was impressed by him…"

Read the Full ArticleDiscussing Steve Grossman (4): Interview with Jerry Bergonzi

“He really had great time feel, great technique, played with great authority and energy. He was just a natural saxophone player… Everybody admired Steve.”

Read the Full ArticleDiscussing Steve Grossman (5): Interview with Damon Brown

“After three or four days, one minute he’d be sounding like Sonny Rollins… What he really wanted was for the band to be free…”

Read the Full Article